In late 1958, during heightened tensions in the Taiwan Strait, Skyraider pilots were prepped for nuclear strike missions. They spent tense hours at night, seated in their aircraft and ready for catapult launch with nuke bombs, before the mission was ultimately called off…

The Douglas A-1 Skyraider, also known as the “Spad,” was a legendary single-engine aircraft, as well as the last propeller U.S. Navy attack aircraft to disappear from the decks of the Navy’s aircraft carriers.

Renowned for its rugged design and long endurance, the Skyraider had an exceptional payload capacity: even when it carried its full internal fuel of 2,280 pounds, a 2,200-lb torpedo, two 2,000-lb bombs, 12,5 inch rockets, two 20 mm guns and 240 pounds of ammunition, the Skyraider was still under its maximum gross weight of 25,000 pounds.

Conceived during World War II, the Skyraider saw extensive service during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, excelling in close air support, search and rescue, and interdiction roles. However, its ability to carry a diverse array of munitions, including conventional bombs, rockets, and even torpedoes, made it a versatile platform.

Among its variants, the AD-5N was a specialized version of the Skyraider, featuring a widened fuselage to accommodate a crew of four and advanced avionics for precision operations in challenging conditions.

Nuclear attack Skyraider

At the end of the 1950s, pilots of VA(AW)-33 flew AD-5N aircraft off the USS Essex, primarily training for nuclear strike missions. They specialized in low-level, long-range operations, using tech like the Bureau of Ordnance Atomic Rocket (BOAR) rocket and the Low Altitude Bombing System (LABS) bombing system.

Flying just 50 feet above water or skimming treetops on land, missions were top-secret, with each pilot assigned a unique target. Crews of three or four included electronics techs, practicing whenever budget allowed, both in the U.S. and Europe. Real missions were essentially one-way, though their rocket-powered weapon offered a slight survival edge.

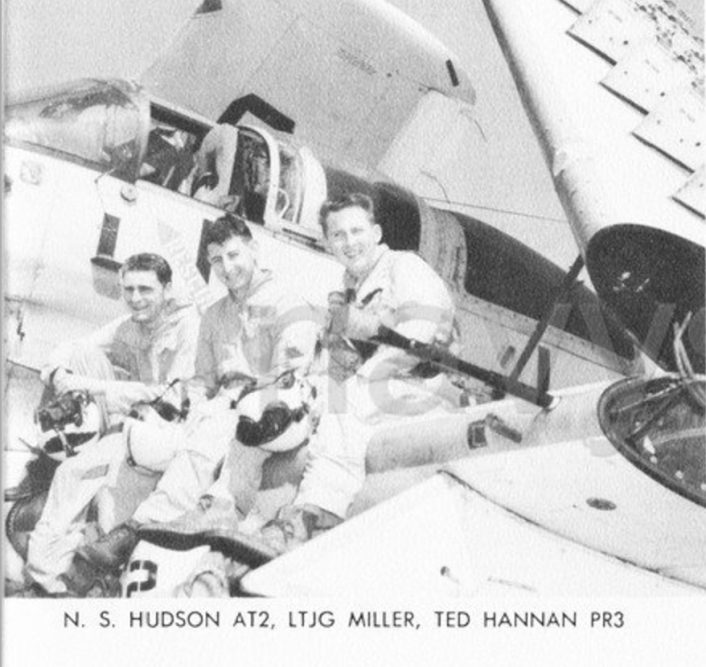

Stephen Miller is a retired electrical engineer, lifelong aviator who spent some time as a Naval Aviator. After flight training, he was assigned to VA(AW)33 in Atlantic City, NJ, flying AD-5N. Here’s what he wrote to us about his time flying the low level long range nuclear weapon delivery mission with the Skyraider.

I joined the Navy right after graduating from Miami of Ohio with a BS in business and was just a few hours short of a commercial certificate at that time. After flight training, I was assigned to VA(AW)33 flying AD-5N in 1956.

In 1957-1958 various detachments consisting of four aircraft were assigned to their respective carriers and were involved in the attendant cruises from time to time. Ours was the USS ESSEX, CVA9. This was strictly during the cold war, between the Korean war and Vietnam.

Our primary mission was low level long range nuclear weapon delivery. This consisted of 50 ft over water and about 150 ft over land (treetop level). All navigation was done using pilotage/dead reckoning and was practised both here and in Europe. There were no radars at that time that could detect a low flying aircraft, due to ground clutter. Our long range cruise airspeed was 160 kts and we’d wait for the engine to sputter before switching back from an empty drop tank to the main. We typically used one or two crewmen to help with the navigation, the same guys (ET’s, Electronic Technicians) who maintained the equipment.

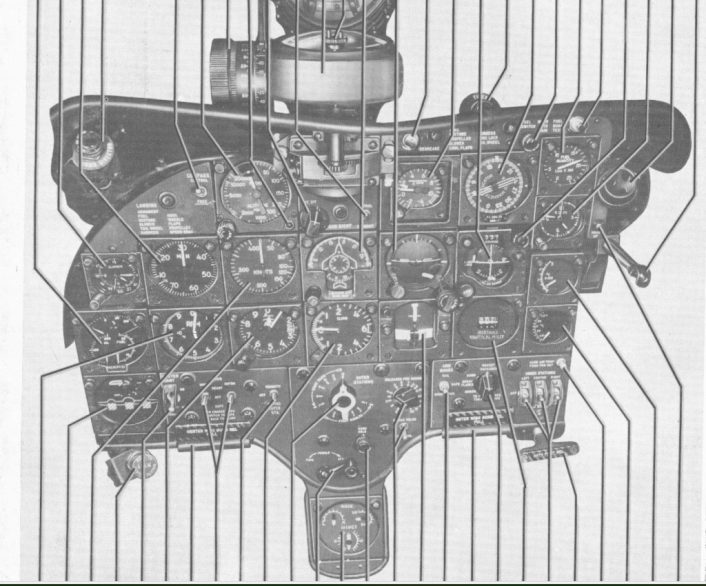

We also had a ground mapping radar, the APS-31, a pod-mounted wing unit.

In mid 1957 we attended a special weapons school in Norfolk VA which covered the operation of the weapon, the Bureau of Ordnance Atomic Rocket (BOAR) and the Low Altitude Bombing System (LABS). They had a working BOAR in the classroom, minus the warhead and we learned how to connect and use the test box to check it out. I was scheduled to make a test run to a simulated target with a live BOAR which had the 1000 lbs of HE (high explosive) used to detonate the nuclear core, but without the core installed. This was ultimately cancelled, but the exercise proceeded without employing the BOAR.

The delivery sequence worked as follows: The LABS contained a timer, accelerometer and a precise gyro heading reference. Just before reaching the IP (initial position for starting the final run toward the release point), the aircraft had to be at max speed (about 240 kts), full or “military” power, limited to five minutes, on heading and maintaining a stable treetop altitude, with the weapon armed.

Upon passing the IP a button on the stick was pressed and the timer would start for the 2-3 minute run. Simultaneously, the vertical nav indicator normally used for VOR/TACAN/ILS LOCALIZER was switched to provide the precise heading reference. At the same time a short panel light and headset tone were activated as well.

When the timer ran out, another short light/tone indicated the aircraft had reached the point to start the launch maneuver. The pilot would then pull and hold the trigger while pulling the nose up in a precise manner using the accelerometer. The horizontal nav indicator normally used for the ILS GLIDESLOPE would switch to this function and initially drop down; it was up to the pilot to raise the nose smoothly to bring the indicator to the center (horizontal) position. This would insure the right amount of “g’s” to produce the desired weapon trajectory upon release, which was automatic when the release attitude was reached.

The BOAR was blown away from the aircraft by the equivalent of four shotgun shells and had a pigtail attached to the airframe which would stretch out and then pull out of the back of the weapon, starting the rocket motor. This weapon had a top speed in the 400kt range and covered a distance of about 7.5 miles.

At this point the AD-5N was entering the initial entry into a loop but was too slow to make it over the top, requiring a wing over to end the maneuver, pickup speed and reverse direction. This was a modified version of a maneuver called a “half Cuban 8”, in this case known as the “idiot loop”.

For propeller driven aircraft the completion of the loop was only possible by a more capable airplane like the single seat AD6, for example. Use of a rocket powered weapon would allow the aircraft to escape the blast zone but the enormous shock wave would have unpredictable results. Some nuclear weapons were unpowered bombs, such that no escape from the blast was possible if delivered in this manner by a propeller driven aircraft. No one was expected back from these missions. Fortunately it never became necessary.

On a Mediterranean cruise during the 1957-58 period we did have a night drill to get a live BOAR ready for launch, but that’s as far as it went, at least for our squadron. At one point we were each assigned top secret targets following background checks for this purpose. These targets were planned and the charts supplied by some unknown source, at least to us, and the zig-zag routes highlighted as well. My best guess is this came from the Pentagon. They were kept in a locked safe with individual combinations. We were required to study our respective routes in our spare time and no one knew what anyone else’s target was. These were strictly visual day missions, though we would probably launch at night in time to reach the beach by daylight. We did have the advantage of radar assist, at least to pick out prominent features like lakes/rivers etc, as well as crewmen to help look for check points. The biggest problem we faced was the fact that the charts over enemy territory were known to contain errors. This only added to the difficulty of attempting to navigate using pilotage/dead reckoning at treetop level in the first place!

In late 1958 during the Quemoy/Matsu island crisis, we were in that area and a friend of mine was there as well with a Pacific fleet squadron flying AD6’s. He sat for two hours on a dark night in his aircraft, hooked up to the catapult, ready to launch with a nuke until they finally called it off. I doubt that this is widely known. That nuclear bomb was a Mark 7 unpowered device. It was a standard nuclear bomb of that time, the yield determined by the size of the nuclear core. A typical mid range core was 18-22 kilotons, about the same as the one dropped on Nagasaki.

Other Navy/Air Force squadrons flying various types of aircraft (primarily jets) had other delivery methods as well. This was our particular experience.

After his tour as a naval aviator Stephen spent a few years in aviation doing charter and flight instructor work flying all the usual single/multi engine aircraft, a stint with Mohawk Airlines flying Convair 240/440 aircraft and ultimately had his own business as an FBO.

I eventually left the aviation industry to pursue a degree in electrical engineering, though I continued flying part time, graduating from Umass Dartmouth in 1967. My career as an engineer subsequently encompassed working for a variety of employers in both design and management, commercial and military and for both large and small firms. My duties often included serving as company pilot as well. One such firm was an autopilot manufacturer which introduced me to that particular industry as well.

In later life I spent some time with the CAP, but now at age 90 I haven’t been current for about 20 years. Hopefully, the information I’ve submitted will be of some historical value to those interested in the Cold War period of the 1950s.