Looking like a holdover from the First World War, this flimsy, antiquated, and slow biplane was all Great Britain had to throw against the mighty German Battleship in one of the greatest sea chases of all time. And in the end, the Swordfish was just what was needed.

Sleek, fast, and heavily armed, Bismarck was the newest battleship of the German Navy. She carried eight 15-inch main guns in four main turrets, two forward and two aft. The Bismarck’s main guns had a range of over 22 miles. In addition she carried twelve 5.9-inch guns, sixteen 4.1-inch guns, along with sixteen 37 mm guns. She also housed between 4 and 6 Arado Ar-196 floatplanes.

Her armor was up to 14 inches thick, and she was over a sixth of a mile long. A beam of over 118 feet made for a stable gun platform, and she had the latest in targeting and fire control systems. Fully loaded the ship displaced over 50,000 tons. All of these factors made this battleship a match for any other vessel on the high seas.

Attempted Breakout

In the black of night on the early morning of May 19, 1941, the German Battleship Bismarck weighed anchor and headed out to sea. Leaving Gotenhafen in occupied Poland, she was to head for the open Atlantic and commence commerce-raiding against merchant ships suppling Great Britain from North America. This would be her first operational voyage, and secrecy was essential to escape undetected.

Bismarck would rendezvous with the cruiser Prinz Eugen later that morning before leaving the Baltic Sea. The two ships would have to snake their way through the Danish Isles and along Norway and Sweden attempting to stay as far as possible from shorelines in hopes of not being spotted before reaching the North Sea.

On May 20, while moving toward Norwegian waters near Sweden, the Bismarck, Prinz Eugen and their escort ships, were spotted by a Swedish cruiser, the Gotland around 1 P.M. This was exactly what the Germans hoped to avoid. Sweden was a neutral country, but teaming with spies and informers. In a matter of hours the British knew where the ships were.

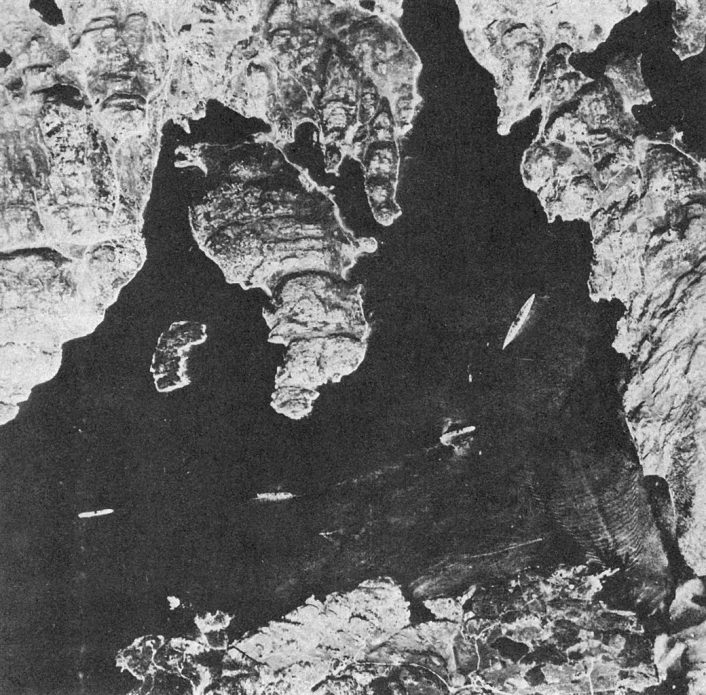

The next day on May 21, 1941, the two ships entered a Norwegian fjord in order to refuel Prinz Eugen. In a decision that was to later haunt the Germans, the Bismarck did not top off her tanks. The ships spent the day under clear skies and at approximately 1:15 P.M. a British Spitfire aircraft performing reconnaissance photographed the ships. Once again their exact location was known by the British.

On May 21, suspecting an attempted breakout by the Germans, the British had the cruiser Norfolk on patrol in the Denmark Strait, and another cruiser, the Suffolk in route to join her. The battlecruiser Hood and the battleship Prince of Wales were ordered to sail from Scapa Flow to the Denmark Strait in order to intercept the German vessels. Battleship King George V, battlecruiser Repulse, and the aircraft carrier Victorious were ordered to be ready to sail as well on short notice.

Early on the morning of May 22, the escort ships departed and Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were now alone and moving towards open seas. Bad weather was in the Germans favor, with rain, overcast skies, and fog cloaking the ships. Bismarck’s camouflage stripes and false bow and stern waves had been painted out and she was now a dull grey, allowing her to blend in perfect with her surroundings. The plan was to make for the Denmark Strait between Iceland and Greenland and break out into the open Atlantic.

A reconnaissance flight by the British revealed the German ships had departed the Norwegian fjord on the evening of May 22, 1941. At 10:45 that night the British fleet left their home base of Scapa Flow. The force included the King George V, Victorious, the cruisers Aurora, Hermione, Kenya, and Galatea, and several destroyers. Repulse would also join this force as well. The British had placed forces in all the possible breakout routes to intercept the Bismarck. A showdown was coming.

High Noon on the High Seas

Still concealed in bad weather on May 23, 1941, the German ships continued toward the Denmark Strait, entering and only having the weather clear, now favoring the Norfolk and Suffolk on patrol there. The two British cruisers found their prey, and began shadowing the Germans. As Suffolk stalked the behemoths outside the fog bank, Norfolk raced to join. However the captain misjudged and came out six miles in front of the Bismarck. Five salvos straddled the Norfolk as Bismarck fired her guns in anger for the first time. The concussion from the huge guns being fired knocked Bismarck’s forward radar out causing her to go blind looking forward. Prinz Eugen was ordered to take the lead. The Hood now received word of Bismarck’s location, and along with Prince of Wales rushed to intercept.

At 5:45 A.M. on the morning of May 24, the leviathans found each other after a continuous cat and mouse game between the British cruisers and the German warships, often losing track of one another. The Hood opened fire at approximately 5:53 at a range of around 13 miles, taking aim at the lead ship, Prinz Eugen, mistaking it for the Bismarck. The shots missed their mark, and the captain of the Prince of Wales realized the wrong ship was being targeted and opened fire on the Bismarck. Bismarck responded in kind firing three salvos at Hood before finding her mark. The forth salvo struck home, piercing the lightly armored decks and igniting an ammunition magazine. The Hood exploded, breaking in two and sinking in a matter of minutes. Only three men out of a crew of over 1,400 survived the destruction of the Hood.

Meanwhile even the Germans could not believe their eyes, the pride of the British fleet, the Hood, was gone. Bismarck and Prinz Eugen then turned their guns towards the Prince of Wales, pummeling the ship until she had to withdraw. Prince of Wales was a brand new ship, still working out teething problems and had civil contractors on board that day.

The Bismarck received damage in the battle also; a hit forward was causing her to be down by the bow, and another hit below the torpedo belt caused some flooding and a shutdown of the port side boiler room. Bismarck’s top speed was now reduced from close to 31 knots to 28 knots. The Bismarck would have to put in for repairs at St. Nazaire in occupied France. After sudden maneuvering during the evening of May 24 by the Bismarck and her firing at the British stalkers, Prinz Eugen was released in the chaos unnoticed to continue commerce-raiding. Now the British aircraft carrier Victorious was 120 miles away and the only vessel that could slow down the Bismarck.

Enter the “Stringbag”

Victorious was a newly commissioned ship with an inexperienced crew. On board she carried 9 of the three-seater Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers. Fixed wheeled biplanes with open cockpits and a top speed of only around 120 mph, the Swordfish carried one torpedo and one forward firing .303 in machine gun and also a machine gun mounted in the aft cockpit. Looking like a relic from the First World War and built with wings and parts of the fuselage covered with fabric, they were affectionately known as “stringbags” The biplane wings folded for storage and they were powered by radial piston engines.

At 10:00 P.M. on May 24, in poor weather and with a heaving flight deck, the 9 Swordfish took off from Victorious. Finding the target, hitting her, and getting back to the carrier in bad weather seemed impossible. Landing on the pitching deck was even more of a wing and a prayer if they did make it back. Many of the Swordfish crew were new and had not experienced these conditions or landed on a carrier at night. It seemed like a suicide mission.

One and a half hours later the radar of the flight leader’s aircraft picked up a ship, and led the group down to the target only to realize it was an American Coast Guard Cutter, the Modoc. The mistake was realized but not before the Bismarck had discovered the attacking planes and began firing at them.

The Swordfish regrouped and pressed their attack on the Bismarck. The aircraft came in low, just above the wave crests, and the Germans were firing everything they had at them. Even the 15 inch main guns were shooting at the flimsy biplanes, causing huge waterspouts all about, at one point a huge splash hit the leader’s plane, lifting it up and tearing the bottom out. It flew on anyway launching its torpedo.

The anti-aircraft gunners on the Bismarck had fired and fired at the Swordfish, but could not score any hits worthy of bringing them down. One British torpedo scored a hit on the Bismarck in the armor belt causing little damage. The attackers flew off into the growing darkness.

The “stringbags” flew 100 miles back to the carrier, not a single plane had been lost, but many damaged. The homing beacon stopped working on the Victorious, and aircraft were low on fuel. If they did find home, they’d get one shot at landing before fuel ran out. Finally a red lamp was sighted on the Galatea that was sailing with Victorious. They had found the ships. Miraculously all nine aircraft safely touched down, even those piloted by novice pilots. One engine ran out of fuel the minute it hit the arrester wires, and the gunner of the plane hit with the huge splash from the main guns was almost frozen, ridding home with his feet dangling over empty space where the bottom of the plane once was.

Bismarck sailed on, but the maneuvering in attempt to avoid the torpedoes had caused some temporary repairs to come lose and leak again. This slowed the ship again, now down to 16 knots while repairs were being made. Other British ships were steaming at full throttle to intercept her, consisting of King George V and Repulse. And the Bismarck still had that pesky shadowing force following her as well.

On May 25 at around 3 A.M., the Bismarck went hard starboard disappearing from Suffolk’s radar, made a huge loop to the north, then back east, crossing the wake of the British ships and headed towards France. The British had lost the Bismarck again. Several mistakes and miscalculations led to the British placing forces in the wrong areas trying to outguess Bismarck’s intentions and how damaged she might be. It looked like the Bismarck, crawling along at 20 knots because of damage, leaking oil, and the crew regretting not topping off the tanks in Norway, would still make it back to France and the cover of Luftwaffe bombers. The German’s luck would not hold however.

At 10:30 A.M. May 26, 1941, the Bismarck was spotted by a PBY Catalina flying boat. The PBY went into the clouds and circled back down for a closer look, misjudging their position and breaking out of the clouds right above the ship. The Bismarck opened fire shaking the flying boat and raking her hull with shrapnel. The PBY sent word back they had found the German battleship. A chunk of the aircraft was blown away from between the pilots seats allowing them to see daylight below, and when the Catalina finally got back to base, a half dozen holes were counted in the aircraft, but no injuries to the crew occurred.

The British once again knew the Bismarck’s whereabouts. The problem was, only one weapon was in place to be effective, another aircraft carrier carrying Fairy Swordfish, the Ark Royal. She was a mere 50 miles away. This was the last chance to stop the Germans and the British must now rely on the same aircraft that had failed in the previous attack. It seemed a miracle was needed.

A solitary Swordfish was now constantly trailing the Bismarck, alerting her crew that a carrier had to be nearby. The aircraft stayed just out of gun range, and when one left, another took its place. The Germans waited for the anticipated attack.

Early in the evening on May 26, the Ark Royal launched her 15 Swordfish. The aircraft detected a ship in area the Bismarck was thought to be in and dived and attacked. There was no return fire, and the ship had two funnels, something not found on the Bismarck. Upon returning to the carrier, the pilots discovered they had attacked one of their own ships, the cruiser Sheffield. No damage was done, as several torpedoes malfunctioned and exploded when hitting the water, with the Sheffield dodging the rest. Only three pilots recognized the ship and did not drop torpedoes. Now the planes had to rearm and refuel and go back out and search for the appropriate target, but the weather was turning against them. The faulty torpedo triggers were replaced with a more reliable type. A German U-boat sat by watching the Ark Royal and Renown sail past, out of torpedoes from a convoy raid, helpless to stop them.

The second raid was launched at 7:15 P.M., all 15 Swordfish flew off towards their prey. This would be the final chance to stop the Bismarck before she reached safe waters. They found the target at around 8:30 P.M. and pressed home the attack.

The planes were attacking more recklessly than before, realizing this was the final opportunity. They came in low in pairs. Once more the mighty German ship opened up with all she had, including her main armament, again without striking any of the aircraft and knocking them out of the sky. Orders constantly changed in the engine room as the ship attempted to dodge the barrage of torpedoes. Fifteen minutes into the attack, two explosions occurred on the Bismarck in quick succession. The ship continued on.

Late into the attack two aircraft came in on the port beam, turned right, and flew in too low for the guns to bear on them. Two torpedoes were now in the water heading for the Bismarck’s stern as she made a turn to port. Then there was an explosion aft. The rudder indicator showed left 12 degrees. It stayed there. Bismarck had been hit in her most vulnerable place, the rudder, and it was now jammed at left 12 degrees. The ship could now only travel in one large continuous circle, taking it right into the teeth of the British fleet. Attempts to repair the rudder and to steer with propellers failed, the wind curtailing the latter efforts. She was now a sitting duck. The British got their miracle. All 15 aircraft returned to the carrier, some of the damaged planes crash landed, but none had been shot down by enemy fire.

The Death Knell

On the morning of May 26, the British forces and the Bismarck came into contact with one another. The British had Rodney, King George V, and the Norfolk on scene, and later would be joined by the cruiser Dorsetshire. Out-numbered and unable to maneuver, Bismarck was pummeled by the British ships. She was reduced to a flaming hulk, her guns fell silent and her decks were covered in carnage. But she was still afloat. The British moved in with torpedoes for the final kill. Minutes later the Bismarck’s stern went down and then she slipped below the waves and was gone. It is of great debate as to who actually sank her, the British claim they did, but the Germans insist they set scuttling charges and sank her to avoid her capture.

An Unlikely Hero

The Bismarck took from 1936 to 1940 to be completed and commissioned. Her first and only operational voyage lasted a mere eight days. The battleship’s anti-aircraft guns had failed her because the targeting and fire control systems were designed to track newer, faster aircraft; hence, the slow and low flying biplanes were immune to the new technology. An aging, fabric covered, puny biplane in one unlikely shot had just stopped a 50,000 ton modern state-of-the-art warship bristling with the newest weapons and guidance systems, thus completely altering the war in the Atlantic and preventing carnage that could have been dealt to merchant shipping. The weapon the British had the least confidence in and appeared the feeblest had indeed performed a miracle.