USAF, Navy and Marines Struck Back at Qaddafi’s Libya for Terrorist Bombing.

Their swing-wings straining to lift a heavy bomb load, the afterburner thunder from an air-armada of twenty-four F-111Fs startled motorists along the B1112 highway and Brandon Road in the English countryside. Aircraft spotters would know that F-111Fs carrying live Mk. 82 Snake Eye high-drag bombs and GBU-10 Paveway II laser guided bombs wasn’t normal. This much jet noise around RAF Lakenheath was unusual for this time of day. Something was happening. Something big.

The action had started moments before, over at RAF Mildenhall and RAF Fairford. The jet engine shriek of giant, aviation fuel-bloated KC-10 and KC-135 tankers filled the air as twenty-eight of the lumbering grey monsters used most of their runways to get airborne and struggle up into the darkening dusk. It looked like a lot of planes for a “training exercise”.

Hours later, on station in the Mediterranean, the aircraft carriers U.S.S. America (CV-66) and U.S.S. Coral Sea (CV-43) came about to put the wind over their bows and down the deck in preparation for flight ops. Their catapults sweated steamy tendrils at the squat haunches of gawky-looking A-6 Intruders, wings bent under giant loads of iron dumb-bombs. Behind the retracting jet blast ramps on the flight deck, a new aircraft, untested in battle, sat in wait. Pointy-nosed and twin-tailed, the tips of her wings were still folded upward. This would be the moment of reckoning for the sleek, new F/A-18 Hornet. She holstered a new kind of radar killing, beam-riding missile called the AGM-88 High Speed Anti-Radiation Missile, or “HARM” along with the combat-proven AGM-45 Shrike radar killing missiles.

From as far north as England to the southern Mediterranean a massive air and seaborne trap had been sprung. Now its jagged steel jaws began to swing shut with gathering force on its quarry: Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya. These were the beginnings of the Tuesday, April 15, 1986 Operation El Dorado Canyon, the U.S. retaliatory strikes on Libya.

With dark, squinty eyes, a scrubby goatee, a pale, saggy, pockmarked complexion and a perpetual scowl, Muammar Qaddafi looked more like a villain from a Bond movie than the president of an oil-rich African nation. His penchant for melding military uniforms with super-hero costumes made him a harsh parody of himself even in the African world of opulent dictator regalia. He frequently wore a full-length cape. Some of his military “decorations” included weird photos pinned to his uniform. He held court over subjects who were granted an audience while presiding from an assortment of custom made, gilded thrones. He traveled with a legion of female bodyguards who doubled as concubines in cocaine and booze-fueled orgies. Everything about Qaddafi was bizarre, overstated and difficult to take seriously. Except for his reign of terror.

Qaddafi’s clandestine intelligence organizations had waged an unconventional war against U.S. interests throughout Europe and the Middle East for years. The combat manifested itself in terror attacks on civilian and military targets, culminating in the Le Belle discotheque bombing in West Berlin on April 5, 1986. Two U.S. Army sergeants died from the bombing, Sgt. Kenneth T. Ford, killed in the bombing, and Sgt. James E. Goins, who died of injuries sustained in the blast two months after the attack.

American President Ronald Reagan quickly ordered a retaliatory strike against Libya for the West Berlin disco bombing that killed 2 U.S. servicemen and injured 229 more. Only two weeks later, Operation El Dorado Canyon began.

Operation El Dorado Canyon was more of a logistical challenge than a military one. Because of a raft of diplomatic disagreements over how the Libyan affair ought to be handled, the strike force could not overfly France, Spain or Italy on its way to targets in Libya. Even today some people mistakenly believe the F-111F strikes from Lakenheath were prohibited from overflying France because then-President Francois Mitterrand opposed military action against Libya. In fact, the opposite is true. President Mitterrand advocated a full-scale military intervention that would permanently remove Qaddafi from power. He was opposed to the measured U.S. response of only using air strikes against military targets.

Interestingly, there was a well-developed plan to hit Libya using the then-classified F-117 stealth fighter. It was scrapped in the eleventh hour in favor of using the long-range F-111F and Navy/Marine carrier based strikes partially out of concern for risking the secret F-117s over Libyan airspace.

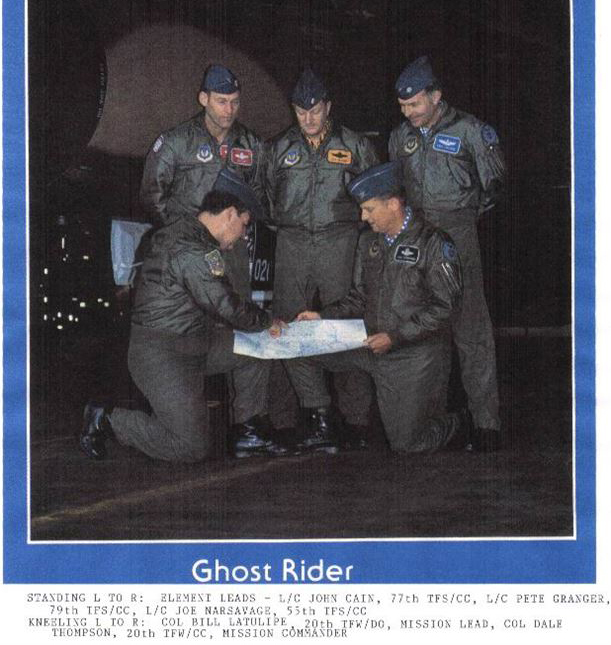

Rehearsals for a long-range F-111F strike on Libya as a contingency plan for the F-117 raid had already been conducted across the Atlantic from east to west in October 1985 by the 20th Tactical Fighter Wing. The practice raid, called Operation Ghost Rider, began from RAF Upper Heyford using earlier model F-111Es. The rehearsal confirmed the mission template for the actual Operation El Dorado Canyon as viable. The USAF 48th Tactical Fighter Wing would fly the operational Libyan strike using the updated F-111Fs equipped with (then) advanced Ford Aerospace AN/AVQ-26 Pave Tack electro-optical targeting pod. Video recorded from the Pave Tack pods during the strikes featured prominently in U.S. news broadcasts after the raid, beginning the media convention sometimes called “kill TV” that went on to become widespread during the later Gulf wars.

The U.K. based U.S. Air Force strike also included five EF-111A Raven electronic warfare aircraft from RAF Upper Heyford’s 42nd Electronic Combat Squadron. These aircraft provided a haze of electronic jamming against radars and communications around the target area to help conceal and protect the F-111F strike force.

The combined force of F-111Fs and EF-111As would hit Bab al-Azizia military barracks with thirty-six 2,000-lb. laser-guided GBU-10 smart bombs. Another part of the F-111F force would use GBU-10s to strike Murat Sidi Bilal, a training installation for Libyan underwater demolition teams and special operations forces. The third section of the F-111F strike force would use Mk82 unguided “dumb” bombs fitted with spring-loaded aerodynamic braking vanes called Snake Eyes to hit a series of Libyan Air Force Ilyushin Il-76 transports parked at Tripoli Air Field. It was these strikes on the Libyan Il-76s at Tripoli that produced the dramatic images of bombs streaking toward their targets with lethal accuracy.

As the Air Force strikes unfolded, the U.S. Navy carrier-based strikes would employ A-6E Intruders to bomb targets at Jamahiriyah Barracks in Benghazi and Benina Airfield while A-7E Corsair IIs and F/A-18 Hornets flew the air defense suppression “wild weasel” mission to protect the A-6E bomber force.

The combined strikes came off almost exactly according to plan and were largely effective, nearly killing the Libyan Leader, Qaddafi, himself. Qaddafi was only able to shelter from the strike allegedly after receiving last minute advanced warning from then-Italian Prime Minister Bettino Craxi via the Libyan Ambassador in Rome, Abdul-Rahman Shalgam.

While the majority of the targeting and weapons delivery was very accurate, there were several misses during the raid. These produced a number of civilian casualties that remain disputed to this day. One claimed that Muammar Qaddafi’s adopted daughter was killed or seriously wounded in the raid.

During the raid, Capt. Fernando Ribas-Dominicci and WSO Capt. Paul F. Lorence, flying F-111F tail number 389 and callsign Karma 52, were shot down off the coast of Libya becoming the only casualties of the entire operation. Capt. Ribas-Dominicci’s body was eventually returned by the Libyan government in 1989, however the location of Capt. Lorence’s remains is still currently unknown.

Following the strike, which only lasted twelve minutes, U.S. President Ronald Reagan delivered a stirring live television address that included a pointed message for Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi. Reagan, in his best actor’s inflection, looked directly into the television camera after a dramatic pause and told the world that Qaddafi had, “…counted on America to be passive. He counted wrong.” It was a memorable moment in the Reagan presidency.

Operation El Dorado Canyon was the shining moment of the F-111’s legacy. The aircraft, originally endorsed by former defense secretary Robert McNamara as a sort of early “joint strike fighter” concept, was rejected for use by the Navy for a raft of technical reasons. Despite its “F” for “Fighter” designation, the F-111 was a bomber, in much the same way the F-117 was never a fighter and the modern F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is mostly a tactical strike aircraft, but with air-to-air capability.

In development, the F-111 concept had bloated in size and weight at the cost of air-to-air capability and maneuverability. In the early Vietnam conflict, the first deployment of F-111s to Southeast Asia had been disastrous. Three of the first six sent to Vietnam in 1968 crashed due to problems with the complex variable-geometry swing-wings. A later re-introduction of F-111s during 1972 in Vietnam was significantly more successful. The aircraft flew low-level night attack missions in advance of B-52 strikes. The F-111’s long range, excellent low-altitude performance and extremely high speed made it largely immune to even the advanced North Vietnamese air defense network. During its second deployment, only six F-111s were lost in approximately 4,000 missions. Considering the massive losses of almost half of the USAF F-105 Thunderchiefs in Vietnam, the F-111 eventually redeemed itself as a credible strike aircraft despite the Navy’s rejection and the early losses.

But it took Operation El Dorado Canyon to truly emboss the F-111 in the tapestry of U.S. air combat history. The aircraft eventually transitioned to the “FB-111” with additional length, upgraded engines and a new home with the Strategic Air Command. Finally, the F-111 ended its career in U.S. service in December 1998 as the EF-111 Raven electronic countermeasures variant used in Operation El Dorado Canyon. The EF-111 Raven went on to fly the last F-111 missions in Operation Desert Storm before its retirement from U.S service in 1998. The Royal Australian Air Force also used three versions of the F-111 called the F-111C, F-111G (training variant) and the RF-111C reconnaissance version up until their retirement in December, 2010.

Operation El Dorado Canyon could be seen as the beginning of the end for Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi. A number of further skirmishes with the U.S. followed in subsequent years including, most sensationally, the January 4, 1989 Gulf of Sidra incident (one of several “Gulf of Sidra” incidents) that involved two U.S. Navy F-14A Tomcats of VF-32 “The Swordsmen” from the USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) shooting down a pair of Libyan MiG-23s. The real-life Gulf of Sidra incident closely mirrored the 1986 Hollywood film, “Top Gun”.

In his final, typically cinematic act, Muammar Qaddafi was killed on October 20, 2011 as the Arab Spring reached Libya. A mob of Libyan National Transitional Counsel members fighting the Battle of Sirte discovered a fleeing and disheveled Qaddafi hiding inside a drain pipe. Qaddafi was discovered by, what else, a man with a golden gun named Omran Shaban. Qaddafi’s despotic, and dramatic, reign was finally over, 25 years after the Operation El Dorado Canyon raids that happened on this day in 1986.